The collective memory of Rawdon’s citizens includes the tragedy exposed in this text recounting a tragic episode in our history. Over the years, some of the facts have been distorted or invented, but they remain alive. The following presents the contemporary vision of a dark spectre of madness.

Ignorance, material and spiritual poverty, and isolation form the basis of this sad story.

This account is meant to show compassion for the Nulty family and is set in a historical context that is far different from current times.

The story begins in 1897 and comes to a tragic end in 1898. But in fact, the real beginning of the story goes back to the arrival in Rawdon of a wave of Irish immigrants around the 1800s. Many of them thought that this exodus would lead to an improvement in their living conditions.

During those years of great darkness, in a rural Rawdon, those less well-off were in a perpetual fight for survival. Without dying of hunger, their hopes for prosperity sank amid their monotonous and difficult daily lives.

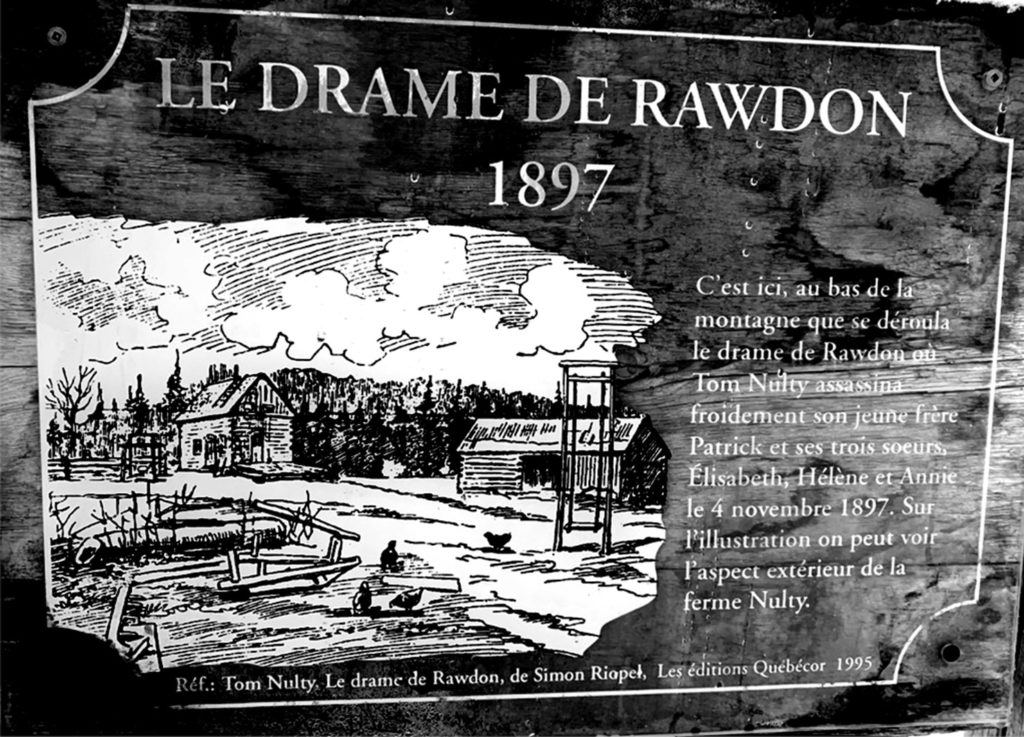

The Nulty family in Rawdon

Alexander Nulty (1804-1877) and Margaret Daly (1818-1887) were among the cohort of Irish immigrants who arrived in Canada in the 19th century. They were already married, and their son Michael was born in Rawdon on August 17, 1839.

In 1870, this Rawdon resident of Irish origin married a French Canadian named Émilie Ricard, who was born on January 16, 1847. The marriage would yield nine children. Life was hard for these illiterate, boorish and uncouth farmers. Almost entirely self-sufficient, with very basic methods of operating their farm, the Nulty family survived day to day without any hope of improving their lot. This subsistence economy enabled the family to frugally feed their numerous children.

The context of the tragedy

The eldest son Thomas, called Tom, aged 21 years, would spend his energy on avoiding the labour inherent in operating the family farm.

A good dancer, adept on the violin, Tom envisioned his life as a succession of pleasures.

Always first at the table to stuff his face thanks to the work of the others, he would then disappear as soon as he was full.

In a rare flash of new ideas, Tom came up with a plan to marry and settle in his paternal home with his sweetheart.

With his focus limited to his basic needs, he asked his parents’ permission to marry and settle in with the family. Michael Nulty refused this request, explaining that, with the large number of mouths to feed, he couldn’t afford to add another.

Frustrated, Tom sought a solution to his problem. His incompetence and small-mindedness led him to consider a way to reduce the size of the household by eliminating certain members of the family.

The Event

On November 4, 1897, Tom returned home with rage in his heart. His recently married sister had also refused to accommodate him and his future wife.

When he arrived, a smell of decay filled the dilapidated farm. Here, humans and animals showed the same resignation, with rare hopes deadened by a life of misery.

Determined to make room in the home, a saddened Tom set his aim, pushing away the affection he felt for his brother and sisters.

To make his somber task easier, Tom chose to target the youngest and most vulnerable.

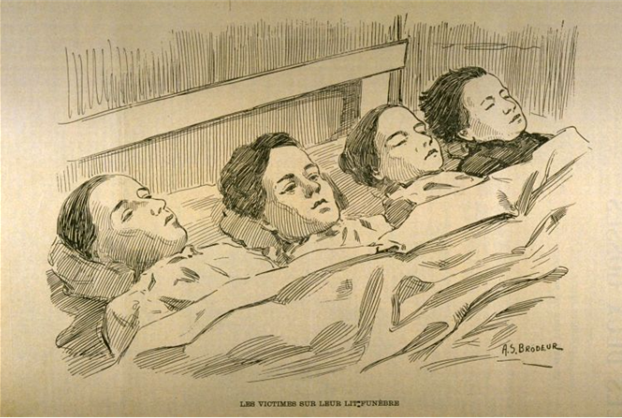

Then, armed with an axe, he exterminated three of his sisters and his younger brother.

His flight was pathetic. With his clothes stained as a result of his wrongdoings, he tried to make up some shoddy alibis. Quickly arrested and quickly judged, he soon confessed and attempted to justify his actions, pretending that he was the victim. He was condemned to death by hanging.

Father Baillargé

Fréderic-Alexandre Baillargé (1854-1928) was the parish priest of Rawdon from 1893 to 1899.

This holder of a doctorate in philosophy met with certain members of the Nulty family before the tragedy and described the depth of their ignorance with indignation. He attempted to instill Christian values in two of the young girls, but the depth of the idiocy afflicting them stirred up a merciful kindness in him.

Still, following the fratricide, he would be among the rare advocates for Tom Nulty. Alluding to Nulty’s mental incapacity, he wrote a letter to the Governor General of Canada, Lord Aberdeen, born in Scotland under the name John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon (1847-1934), to ask him to commute the assassin’s death sentence to life in prison.

Given the Governor General’s refusal to change the nature of his sentence, Tom Nulty was hanged in the Joliette prison on May 20, 1898.

The Death Penalty

More than 3,000 curious onlookers would attempt to attend this execution. It should be noted that, to have the best seats, attendees had to have received an invitation. The dignitaries at the time, those who had received a pass, had good places to attend the hanging.

For the others, any means to get to see the show were good: climbing trees, scaling walls, huddling around windows, to name a few. Morbid curiosity turned this misfortune into entertainment.

When the knell rang, the trap of the gallows opened, and the poor man dangled at the end of the rope until his death.

Tom’s body was buried in Rawdon’s mass grave along with those of his brother and sisters.

In Canada, starting in 1859, the death penalty by hanging was the method used to execute criminals. The death penalty would then be abolished in Canada in 1976.

From 1859 to 1976, there were 710 executions across Canada.

In 1962, the last execution sent Ronald Turpin and Arthur Lucas to heaven or hell.

The survivors

An inexplicable fate resulted in the lives of four of the Nulty girls being spared. Their absence at the farm during Tom’s killing spree allowed for Nulty descendants, without the surname.

Marguerite, Mary, Judith and Catherine married men from the area: Marguerite wed Alexandre Poudrier, Mary wed Francis Vaillancourt, Judith wed Maxime Grenier and Catherine wed Joseph Grenier.

As a result, the blood of the Nulty family continued to run in the veins of several generations.

This text is a tribute to the five victims of the Nulty family:

Elizabeth Nulty, 17 years old

Anna Nulty, 14 years old

Ellen Nulty, 11 years old

Patrick Nulty, 9 years old

Thomas Nulty, 21 years old

References

nosorigines.qc.ca

La Presse, November 8, 1897

La Presse, November 12, 1897

La Presse. November 13, 1897

La Presse, May 20, 1898

BAnQ numérique

L'Étoile du nord, June 2, 1898